By K-Fai Steele

Guest post by the 2018 Ezra Jack Keats/Kerlan Memorial Fellowship recipient. Applications for the 2019 Fellowship are due January 30. Please see z.umn.edu/kerlanfellowships for more information.

Sketchbooks are highly private workspaces; they’re where characters are doodled into being and ideas grow into stories. A sketchbook reveals the ways that an author-illustrator takes in the world, melds it with their perspective and experience, and then creates stories and drawings. Sketchbooks show the artist at their most creatively vulnerable and free and they offer an incredibly intimate way to get to know someone’s work and process.

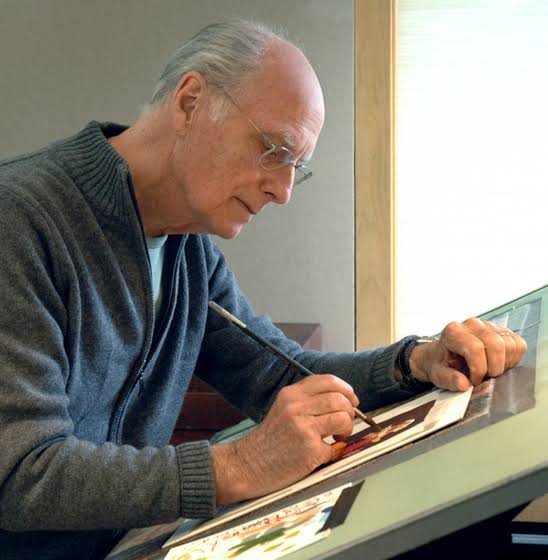

As an author-illustrator it’s particularly thrilling to look through what archivists and curators refer to as preliminary materials or process art; a cataloging term that includes sketchbooks, drawings, dummies, manuscripts, and more. James Marshall kept a lot of sketchbooks. The Kerlan Collection at the University of Minnesota has over 44 of them that span the years 1967-1991. I spent nearly a third of my three-week Ezra Jack Keats/Kerlan Memorial Fellowship on a self-guided tour of 25 years worth of James Marshall’s sketchbooks. I noticed patterns to his creative process and methods, and saw specific ways that his life and the people he loved inspired his books.

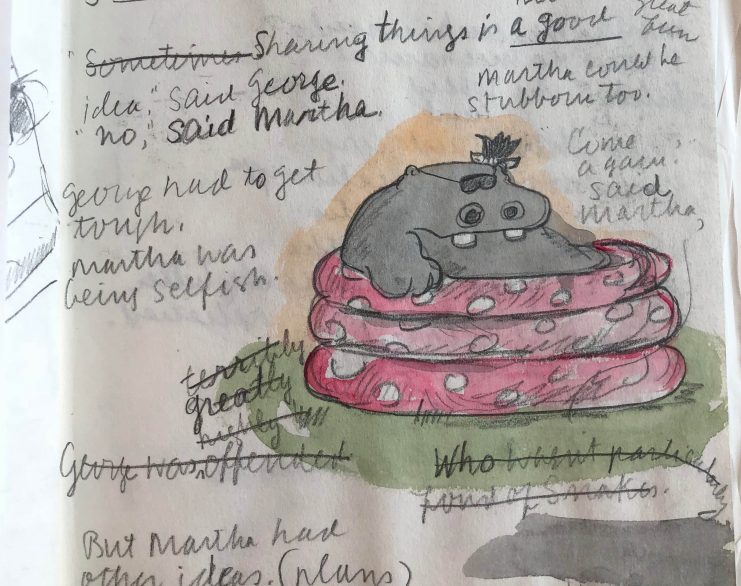

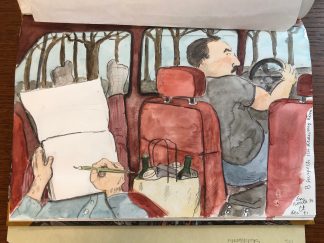

James Marshall was a merciless self-editor and a lot of this work is hashed out in his sketchbooks. Throughout you see him laboring over dialogue and storylines, his pencil crossing our phrases alongside watercolor character sketches. As much as he edited text he edited drawings, often vigorously scribbling out character faces and writing comments next to his finished drawings. His self-doubt is palpable and well-documented in his sketchbooks.

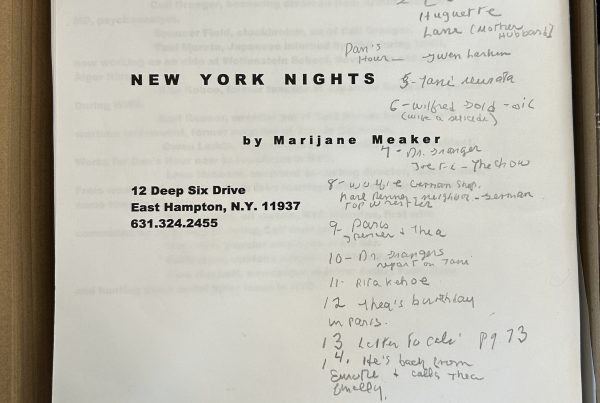

He used sketchbooks to thumbnail stories and work through manuscripts

(many sketchbooks have the title of the book he’s working on written on the cover). Other sketchbooks are mostly to-do lists and budgets. One sketchbook from 1983 was different from the others; it seems to be Marshall’s experiment in keeping an illustrated journal where he synthesizes his activities and what he’s thinking. When looked at closely, this sketchbook in particular shows how he drew on his life for book inspiration:

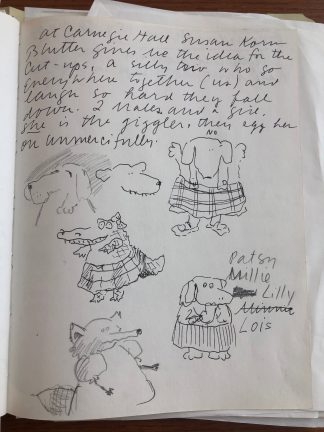

“At Carnegie Hall. Susan Korn Blutter gives me the idea for The Cut-Ups, a silly trio who go everywhere together (us) and laugh so hard that they fall down. 2 males and a girl. She is the giggler, they egg her on unmercifully.”

“Us” and “2 males” it appears, refers to Marshall himself and his partner William Gray, who he refers to throughout his sketchbooks as “B” or “Billy.” The Cut Ups was published in 1984. A later entry describes the three of them going to see a play together with some other friends, “At 91st Street playhouse, one of the best plays in town, Quarter Mariner Terms with Billy, Susan, Ronald, and Adrienne. A falls asleep + snores to the annoyance of others. Susan + I unable to control our laughing.”

This sketchbook shows a certain kind of humor, fun, and mischievousness that can be found in the way that Marshall’s characters like George and Martha, or Fox and his friends interact with each other. It’s also a little Miss Nelson. Marshall’s Troll Country (1980) is dedicated to both Susan and Billy.

Other parts of this journal show Marshall’s life in children’s book author and illustrator circle: a reminder to go to “Ted Gorey’s Diaghilev show” and that “one of Maurice [Sendak’s] prelim drawings for Outside, Over There went for $12,000!” He describes going to New York with Billy and Arnold Lobel (“We get blind drunk”) and in another entry goes to Hillary Knight’s apartment on East 51st Street in New York for drinks and dinner (“largest private record and tape collection I’ve ever seen”). They watch Grace Jones recordings and Marshall writes, “Subjects to avoid in the future–myself, AIDS, and the difference between New York and Los Angeles. The last has got to be the dumbest subject in the world.”

Later that year he travelled by train to Chicago and drew the landscape from his window. He writes, “I love the midwest but hate the very real feeling that I’m in enemy territory.” While I was going through James Marshall’s sketchbooks I corresponded with writer Julie Danielson and author-illustrator Jerrold Connors who have been researching Marshall’s life and work. They mentioned that Marshall died of HIV/AIDS, a part of his life and death which was omitted from his New York Times obituary. Him feeling uncomfortable in the midwest could imply any number of things, but I wonder if it suggests him being away from a safe place of friends and loved ones who knew and loved him for all of the multitudes he contained, including his sexuality. Many of his friends that he mentions in his sketchbooks were also gay, including Arnold Lobel who died of HIV/AIDS in 1987.

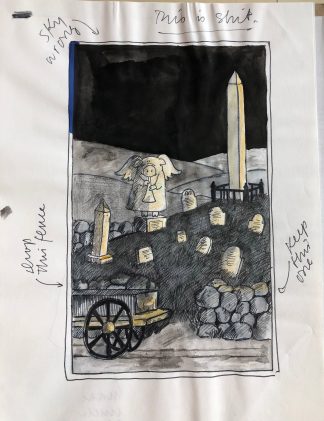

Looking through Marshall’s sketchbooks in the Kerlan Collection was exhilarating. It was also emotionally exhausting, particularly as I went through the sketchbooks he made towards his death at age 50 in 1992 from HIV/AIDS. His sketchbooks at the Kerlan end in December 1991, about ten months before he died. In them he continues to work on manuscripts and sketches and made some more “finished” or labored-over drawings that aren’t quite the style that is found in his books:

Drawing, particularly in a sketchbook, can be a form of documentation; it deepens the time and space for perception. James Marshall’s sketchbooks in the Kerlan Collection are reflective of not only a working artist but a fully real, deeply observant, and thoughtful person; they’re an excellent archive that documents his life and work. Are the things that define an author-illustrator the final books on the shelf? Or are they the preliminary materials in your sketchbooks and your life that allow for those books to be made?

The Kerlan Collection itself is an incredibly special active, living archive; it is constantly changing and growing, and it tells many stories depending on how the material is curated and who’s doing the curation. The collection can show how books reflect politics, history, the artist’s creative process, and more. It can also serve as the most intimate kind of memorial to the most intimate part of picture book making: the sketchbook.

K-Fai Steele (www.k-faisteele.com) is the 2018 Ezra Jack Keats/Kerlan Memorial Fellowship recipient. She is an author-illustrator who lives in San Francisco. A NORMAL PIG is her author-illustrator debut with Balzer + Bray/HarperCollins Childrens (June 2019). She is illustrating NOODLEPHANT by Jacob Kramer with Enchanted Lion Books (January 2019); and OLD MACDONALD HAD A BABY by Emily Snape with Feiwel & Friends/Macmillan (Fall 2019). She’s currently a Brown Handler Writer in Residence at the San Francisco Public Library.

K-Fai Steele (www.k-faisteele.com) is the 2018 Ezra Jack Keats/Kerlan Memorial Fellowship recipient. She is an author-illustrator who lives in San Francisco. A NORMAL PIG is her author-illustrator debut with Balzer + Bray/HarperCollins Childrens (June 2019). She is illustrating NOODLEPHANT by Jacob Kramer with Enchanted Lion Books (January 2019); and OLD MACDONALD HAD A BABY by Emily Snape with Feiwel & Friends/Macmillan (Fall 2019). She’s currently a Brown Handler Writer in Residence at the San Francisco Public Library.

This is an inspiring post on so many levels. I must make time to get to the Kerlan and spend some time with the sketchbooks and process of James Marshall. Thank you!

What a delight to come home from delivering a bag of children’s books to the local food shelf to find this interesting article on THE BLUE OX REVIEW. Thank you.

(I’ve always found much to learn while going through original material at the Kerlan. Years of pleasure…)