By Allison Campbell-Jensen

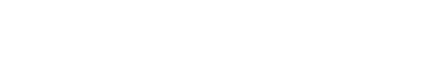

The online world is hosting a wake — for prolific children’s book creator Tomie dePaola, 85, who died from surgical complications on March 30. Thousands of teachers, librarians, authors, and illustrators whom he mentored in classrooms, conferences, and on-line are posting on Twitter, Facebook, and blogs. These messages speak to how Tomie and his work filled the world with his generosity, joy, and kindness.

“To be with Tomie felt like you were his close friend.” says Lisa Von Drasek, Curator of the U’s Kerlan Collection of Children’s Literature. As of the writing of this piece, her Facebook post announcing his death was shared over 19,000 times and had more than 2,000 comments.

Von Drasek wrote:

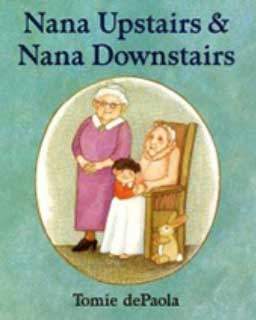

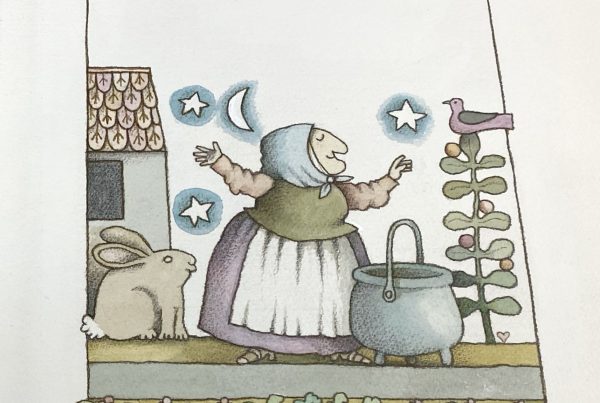

“Perhaps best known for his telling of Strega Nona, Tomie also wrote and illustrated the groundbreaking Oliver Button is a Sissy. Generations of families coped with grieving sharing Nana Upstairs, Nana Downstairs. His early chapter book memoir 26 Fairmont Avenue is the perfect mentor text for emergent readers and writers to tell their own stories. We ask that you share a story, light a candle, read one of his books aloud. May the memory of this righteous one be a blessing.”

Kerlan holds significant collection of dePaola’s work

“He was generous in spirit and action,” says Karen Nelson Hoyle, former Kerlan Curator. “He gave manuscripts for 63 titles and illustrations for 153 titles to the Kerlan Collection.”

Tomie dePaola’s donation to University of Minnesota is one of the treasures of Kerlan Collection, Von Drasek says.

“He had the foresight to keep his original art and to send it to us for safekeeping,” she says. Most importantly, she adds, “He gave us these materials because he knew we were going to teach from them.”

The Children’s Literature Research Collections provides access to these artworks to publishers for reimaging for new editions. Hoyle notes that dePaola even wanted for children visiting the Kerlan Collection to be able to handle the artworks.

An advocate for children’s literature

In matters of education, Hoyle says, dePaola was unofficially mentored by Norine Odland, Professor of Children’s Literature at the U of M. More than 40 years ago, Odland invited him, then known for Charlie Needs His Cloak, to a children’s literature class attended by fourth-grade teacher Karen Carlson.

Carlson says she was captivated by his knowledge and “his sparkle.” She wanted her students to know how a book came to be, so she invited him to her school in Hastings. With the support of the librarian and principal, all the children came in shifts to hear dePaola speak that day.

“He captured every child, every teacher,” Carlson says, who noted that she, her husband, and dePaola became personal friends. And that first author event in Hastings with dePaola launched an Author Day program that continued for 40+ years.

“Whenever he entered a room he would create a hubbub,” Holye says. “He brought both his mother and book editor to the Kerlan to view how well cared for were his original drafts and studies to the manuscripts and art in its final state.” He also spent six weeks at a time in the Twin Cities in the 1980s and 1990s when he worked closely with the staff at the Children’s Theatre Company in Minneapolis to bring to the stage such works as The Clown of God and Strega Nona.

A connection with Kerlan Curator Lisa Von Drasek

Von Drasek had first met Tomie, as she calls him, while working for his publisher in New York City. After she became a librarian, she came to know him better, seeing him at professional gatherings — and he even came to her school. Their relationship grew over the years. When she arrived at the University of Minnesota to head the Kerlan Collection, one of the first things she did was to call him. “Tomie, I got the job,” she recalls. “Your stuff is here. I am so excited!”

He said: “Well, what are you going to do?”

“I’m going to teach,” she replied. “I’m going to share your stuff and your art with children and the students at the U and we’ll make author visits and . . . if that is okay with you?”

“Okay?!” he said “I am thrilled that you are there. I am thrilled you will be sharing my books and art with children!”

Even though Von Drasek was a seasoned professional, she says it meant so much that Tomie also said to her: “You’re going to do great. Call me if you need to.” And she did. “When I was researching grief in picture books, he was my first phone call,”

A pioneer in communicating with children about grief

For more than 40 years, dePaola’s Nana Upstairs & Nana Downstairs has been the go-to recommendation for child experiencing a grandparent’s death. The clear, concise language has spoken to generations of children.

For more than 40 years, dePaola’s Nana Upstairs & Nana Downstairs has been the go-to recommendation for child experiencing a grandparent’s death. The clear, concise language has spoken to generations of children.

“When Tommy was a little boy, he had a grandmother and a great-grandmother,” dePaola wrote. “He loved them very much.”

By naming the protagonist Tommy and using third-person narration, dePaola created authentic, relatable characters. Children can identify with the Sunday visits to the bustling kitchen activities of Nana Downstairs and the calm infirmity of Nana Upstairs.

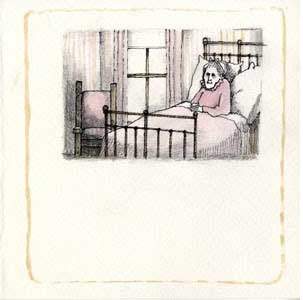

They also are able to share with Tommy his grief when he learns that Nana Upstairs has died. The image of Nana Upstairs’ empty bed is especially poignant. The text reads: “Tommy began to cry. ‘Won’t she ever come back?’ he asked. ‘No, dear,’ Mother said softly ‘except in your memory. She will come back in your memory whenever you think of her.’”

In the original manuscript, dePaola wrote that Mother said that Nana Upstairs had “gone up to where the stars are.” Yet, dePaola said that he took that out because he understood that children would have taken those words literally.

Recognizing that his experience of loss continues to speak to children, dePaola said he was grateful that this book was one that had remained in print. He commemorated the special relationship he had as a child with his grandmother and 94-year-old great-grandmother and by telling his story gave children the opportunity to share their own. When he redid all of the illustrations for a full color edition in 1998, he recalled that he broke down into tears while re-creating Nana Upstairs’ empty bed. “This was indeed written from the heart. As I created the art, 4-year-old Tomie was right next to me.”

While Von Drasek says she appreciated the obituaries that appeared in the New York Times and other media, she was especially touched by Sergio Ruzzier’s observation in the Washington Post.

“In one of the books, Strega Nona’s Magic Lessons (1982), Mr. dePaola seemed to reflect on the nature of his vocation. ‘To learn magic and practice it well,’ the witch tells her apprentice, ‘you must learn to see and not to see. You must learn to remember and to forget; to be still and to be busy. But mostly, you must be faithful to your work.’” As Tomie dePaola always was.

A wonderful article.

I was pleased to see too, the mention of Norine Odland, whose class I took back in the 1970’s. As an adult student, I think we had a special rapport. She helped me plan a meaningful visit to the Kerlan for my Junior Great Books program at Pike Lake School in New Brighton. Tomie would have like that, wouldn’t he?!

Thanks for the memories.